Freehafer Hall, once lauded as example of early open office plan, demolished

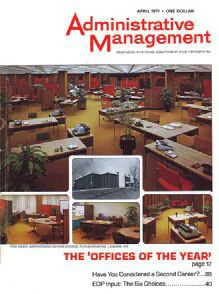

Administrative Management declared the administrative services building the 1971 “Offices of the Year.”

Construction crews quietly demolished Freehafer Hall of Administrative Services over the course of several weeks this winter as part of the State Street redevelopment project slated to plot a new roadway through the site. Although it was razed with little fanfare, when it opened its doors in 1970, the administrative services building (as it was then known) was heralded on the cover of Administrative Management magazine as the “Offices of the Year.”

The open office plan now commonly associated with design enterprises and innovative startups was revolutionary at the time. According to the article, the administrative services building was the first structure in the nation planned from the ground up to accommodate what was considered an unconventional open design.

“The office landscape concept was revolutionary in that it attempted to reduce hierarchy, encourage communication, and support flexibility for change,” says Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler, an assistant professor of design history and author of “Progressive Partitions: The Promises and Problems of the American Open Plan Office” published in the journal Design and Culture.

Typical post-war offices emphasized hierarchy and status. Occupying a private office stood for a certain level of achievement. The larger and more elaborate the private office, the higher one ranked on the organizational chart. Even amenities such as carpet vs. vinyl or a standard desk chair vs. a leather executive desk chair might indicate the difference between a vice president and a director.

“This obsession with encoding hierarchy in space became a source of frustration for organizations not only because it was a pain to manage — nearly every promotion came with a change in space which was expensive and disruptive, but also because it produced workers who were obsessed with the markers of status,” Kaufmann-Buhler says. “By eliminating private offices, the office landscape concept promised to flatten organizational hierarchy and reduce the obsession with status and rank in office design.”

In Freehafer’s case, although there were originally no private, walled offices, the design did have subtle delineations of hierarchy. A secretary typically sat in view of her boss but could not be seen by visitors at his desk. An executive would be allotted a larger amount of workspace, a small meeting table, and a different colored desktop. A handful of directors occupied the rarest of features, a corner.

“It was the most private office I’d ever had, even though it was entirely open,” says Bob Sorensen (M’63, MS M’70, PhD EDU’97), a systems analyst on the team that planned and opened the building. He then worked in the building for 14 years. “It was an interesting experiment in terms of use of space and people’s adaptation to it.”

When viewed on paper, the configuration appears random and chaotic, but proponents of the design argued that organizations were organic entities, not rigid hierarchies. The landscaped office prioritized communication and efficient workflow over compartmentalization by department.

“Workflow at that time was pre¢y paper-dependent,” says Sorensen. “A payroll change required six or seven signatures. By bringing together several departments that interacted with each other, processes functioned more efficiently.”

One casualty of the design was privacy, both real and perceived. “Under landscape you lower your voice,” a manager in the article states. “It even makes reprimands more human.” Although white noise was artificially generated through the airflow system and panels and carpeting were designed to absorb sound, guests in the space were uneasy with the lack of walls. This created a problem for the personnel department when conducting job interviews; walls were eventually constructed to accommodate them.

The slim tabletop desks offered no modesty panels for workers seated at their desks (many in skirts) nor did they provide any deep drawers for women to stash their purses. Hooks were later installed underneath the desks. Workers sliced open their clothes on the sharp desk corners, which were covered with rubber bumpers. The arrangement of freestanding panels, plants, and furniture was touted for its flexibility; however, it was not well-suited for adapting to the personal computer age.

“As we moved into the computer generation, there were heavy cable requirements,” says Sorensen. “The free-flowing flexibility was replaced with a rigid grid system of partitions that could accommodate the necessary cabling.”

The dreary cube farms often derided in popular culture as symbols of dull uniformity actually brought privacy, relief, and personalization to the modern workplace. In an open office, there isn’t a whole lot of space to decorate with family photos and knickknacks.

“The office landscape was a valuable a¢empt at change management,” Sorensen says. “Some people adapted well to it, others were not excited by it. It was a study in systems, but also a study of people and how they work. You need to look at both in order to evaluate its success. It was a lesson in innovation, which in my perspective was worth the effort.”

The general success of the open office was mixed at best. “One of the problems associated with increased communication was the issue of noise and interruptions,” Kaufmann-Buhler says. “New research on office design and productivity conducted in the 1980s found that workers felt more free to communicate with more enclosure rather than less.”

With the rise of the open office as embodied in the tech industry, the merits of the design continue to be debated.

“The same ideals associated with office landscaping as they were described in the late 1960s and 1970s are recycled again and again,” Kaufmann-Buhler says. “The open plan is still described as helping to support communication and encourage interaction, but if you visit these modern open offices, many of the workers have noise-canceling headphones on.

“The greatest testament of our failure to learn from the past in terms of office design is the fact that just as the cubicle has gone out of fashion, some people working in the newest iteration of open-plan arrangements are now thinking that the cubicle design was actually not that bad.”

This story appeared in the Spring 2018 issue of Purdue Alumnus magazine.