New Genetic Testing Available Through ADDL Will Help Dog Breeders Eliminate Specific Diseases

Meng Deng, founder and president of Adipo Therapeutics

Research findings by genetic scientists in the Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine have the power to eradicate specific genetic diseases within certain dog breeds. Testing for the genetic mutations will be offered by the Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL) at Purdue. As the first such tests offered to the general public for three new canine genetic diseases, these screenings will enable breeders to identify which dogs are carriers for a disease and could possibly pass it on to offspring. By ensuring two carriers are not bred together, the disease can be halted before it spreads throughout the breed.

Dr. Kari Ekenstedt, an assistant professor of anatomy and genetics in the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Basic Medical Sciences, holds both a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree and a PhD in mammalian genetics. Her Canine Genetics Laboratory recently solved one genetic disease in Basset Hounds and two genetic diseases in Miniature American Shepherds. All three diseases are autosomal recessive which means the mutated gene is not linked to the sex of the animal and that two copies of the mutation are required to cause disease. In other words, dogs with just one copy of the mutation (“carriers”) are healthy, but should ideally only be bred to clear dogs to avoid producing affected puppies.

“We are excited to partner with Dr. Ekenstedt to provide this testing for animals,” said Dr. Becky Wilkes, head of the ADDL’s molecular and virology sections and associate professor of molecular diagnostics in the college’s Department of Comparative Pathobiology. “Animal genetic testing is a new addition to the ADDL, and we can only provide this service as a result of Dr. Ekenstedt’s expertise in the field. She discovered the genetic changes for which we will be testing that are causing these diseases, which can result in the death of affected puppies. Through this testing and the genetic counseling offered by Dr. Ekenstedt, we will work with breeders to eliminate these genetic diseases in these dog breeds.”

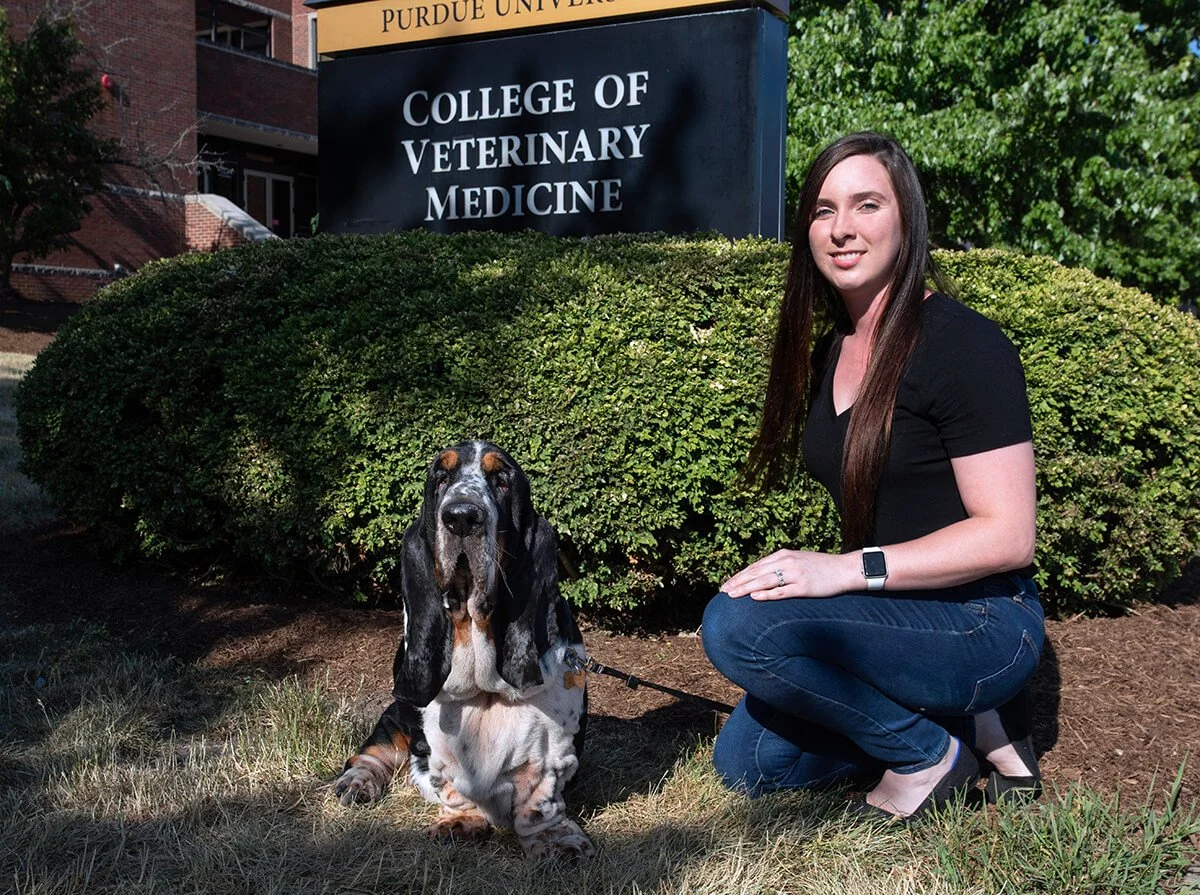

Jeanna Blake, a third-year PhD student in Dr. Ekenstedt’s lab, conducted the majority of research on the glycogen storage disease in Basset Hounds. This disease impacts the body’s ability to store glucose in the liver and muscles and then break it down to create energy. The buildup of glycogen in cardiac muscle can cause dogs to go into heart failure.

“This disease came to my attention after two littermates died quite young from heart failure,” Dr. Ekenstedt said. “The pathologist who conducted the autopsies sent me the tissue, which provided us with a set of sibling DNA that could be whole genome sequenced.”

To solve a genetic disease by identifying a causative mutation, Dr. Ekenstedt’s team uses whole genome sequencing on an affected dog’s DNA and compares it against other whole genome sequences in a database of about 1,000 control samples. Complex computational algorithms sort through billions of pieces of data to help the team narrow down specific genes using an established data analysis pipeline. The entire process can take more than a year.

“I was surprised to discover a novel cause of glycogen storage disease in dogs,” Blake said as she described her role in the research project. “Mutations in the causative gene have been seen in humans, but are new to the dog world. The findings of this study add to the mutational spectrum of glycogen storage diseases in dogs. The more disease-causing mutations we are aware of, the broader genetic testing we can do, resulting in earlier disease diagnosis and disease prevention through targeted breeding strategies. The discovery of and testing for this mutation will allow Basset Hounds to be born free of this specific glycogen storage disease.”

For Jeanna Blake, helping dog breeds like Basset Hounds through canine genetics research is living her dream.

Blake explained that her hope with canine genetic research is to help dog breeders be able to make informed breeding decisions and avoid breeding dogs that have heritable genetic mutations, gradually eliminating genetic diseases from different dog breeds. “I have always wanted to help dogs through scientific research. Having the opportunity to contribute to this groundbreaking research means everything to me. I get to wake up and live my dream every day while contributing to research that directly impacts canine health.”

Blake said knowing that the work being done in the Canine Genetics Lab could prevent even just one Basset Hound puppy from being affected with glycogen storage disease makes all the work worth it. “The impact that this research can have on the dog world further reinforces my commitment to canine genetics. I want to help more dogs through my research.”

The two diseases in Miniature American Shepherds, juvenile onset cataracts and neuroaxonal dystrophy, were largely researched by Dr. Shawna Cook (PU PhD ’23), now a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University. The research was particularly meaningful to Cook, who is the owner of a Miniature American Shepherd.

“I was stoked,” Cook said when asked what her reaction was to having the opportunity to contribute to a research project that has the potential to benefit the breed of dog she has as her own pet. “It definitely pushed this into ‘passion project’ territory. Not only was I given the chance to help dog owners and breeders that I personally know, I was also able to help the breed as a whole. Everyone says that getting a puppy is a lot of work, but my Miniature American Shepherd, Helix, has given that a new definition! Only three years old and she’s given me a lot to do! Without her, I never would have met the owners and breeders who have trusted me to conduct this research.”

Cook’s personal tie to the research proved to be inspiring. “The personal connection that I already had with the breed pushed me to be a better scientist and to take charge of my research,” Cook said. “Weekends, late nights; I was ready at all times to look at data, collect samples, and chat with owners.”

While juvenile onset cataracts aren’t fatal, they are still undesirable for breeders and their clients who both want healthy pets. Neuroaxonal dystrophy, however, causes degeneration in the animal’s nervous system, causing a wobbly gait and progressive worsening until the animal loses its ability to walk entirely.

“These are preventable genetic diseases,” Dr. Ekenstedt said. “By identifying carriers and breeding them with clear dogs, we can keep all the other desirable genetics while completely avoiding the disease. The goal is to test and slowly, over several generations, replace carrier animals. We don’t want to stop breeding every carrier dog immediately because that could have an overall negative effect on the genetic diversity of the breed.”

Cook said both of the Miniature American Shepherd projects were near to her heart. “Being able to tell the breeders that they will able to breed these diseases out of their dogs was simply incredible. Now we can provide the tools needed to aid in the prevention of these heritable diseases. However, there will continue to be inherited diseases, both simple and complex, that exist in our canine companions. No matter the breed, I want to be able to contribute to the breeding of genetically-sound puppies. These projects really cemented the fact that I’m doing what I’m meant to be doing. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.”

Dr. Ekenstedt describes her research as exploratory, meaning the scientists working in her lab aren’t developing a specific hypothesis and then testing to prove or disprove it. Instead, they learn about abnormalities occurring in a certain breed and analyze DNA from affected animals to identify the specific mutation causing the genetic disease.

“Just like humans, animal genomes mutate every generation,” Dr. Ekenstedt said. “These naturally occurring diseases are generated through spontaneous mutations. Many breeders are doing absolutely everything they can to produce healthy dogs, but genetic diseases will still pop up. Having tools to identify disease carriers will be essential to producing healthy puppies, especially in long-established pure breeds with restricted gene pools.”

Many of the student researchers in the lab work on single gene mutations which are typically relatively straight-forward to solve. The lab is also working on several more genetically complex diseases that cannot be linked to a single gene. But there’s one disease — pigmentary uveitis in Golden Retrievers — that Dr. Ekenstedt considers her white whale. She and Dr. Wendy Townsend, professor of ophthalmology in the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, have been collaborating for years to try to crack the genetic code of the disease which affects up to a third of Golden Retrievers.

“The problem with pigmentary uveitis is that it’s painful and inflammatory enough that sometimes dogs end up with their eyes enucleated,” Dr. Ekenstedt said. “We’ve used all the same techniques to analyze the whole genome sequence, but it’s been very tricky to identify mutations. There are a number of reasons why it remains elusive, which makes it a really fun, but also frustrating, puzzle to solve. I would be so excited if we can find the answer because there are so many Golden Retrievers in the world and eliminating that disease would have a tremendously positive impact on the breed.”

With more than 200 dog breeds registered with the American Kennel Club and new breed-specific genetic diseases emerging all the time, Dr. Ekenstedt’s lab will continue solving genetic diseases and offering those tests through the ADDL as they become available. Revenue generated from sales of the tests is funneled back into the ADDL and Dr. Ekenstedt’s lab to fund further research.

Offering genetic testing through the ADDL establishes Purdue’s reputation as a pioneering institution in canine genetics, a somewhat neglected field of research within the profession. Dr. Ekenstedt estimates there are only about a dozen labs in North America conducting canine genetic testing. “I have a crew of brilliant scientists working in my lab,” Dr. Ekenstedt said. “I am confident in our team’s ability to solve many more genetic diseases.”

Kevin Doerr, director of public affairs and communications for the Purdue College of Veterinary Medicine, contributed to this story.

This story appeared in the Purdue Veterinary Medicine Summer 2023 report