OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY’S JEREMY BUSBY ’95 DEVELOPED METICULOUS MENTALITY IN K-STATE’S NUCLEAR ENGINEERING PROGRAM

On a bookshelf in Jeremy Busby’s office, tucked among scientific journals, policy manuals and bric-a-brac accumulated during his nearly 30 years as a nuclear engineer, sits his undergraduate notebook from Applied Reactors Theory I & II. Busby ’95 is now the associate lab director for the isotope science and engineering directorate at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a federally funded research and development center in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He took those courses with Professor Ken Shultis and Professor Richard Faw in 1992 and 1993, but the principles instilled have stayed with him throughout his distinguished career.

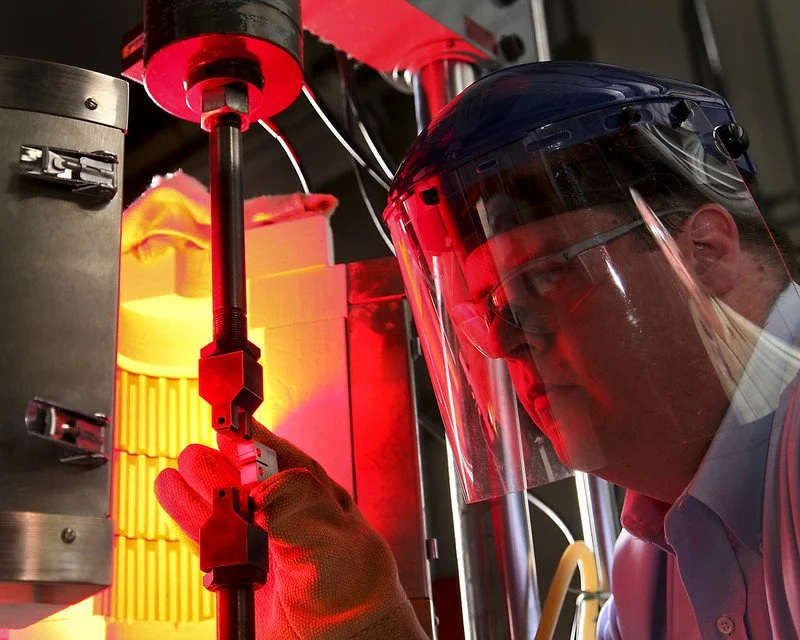

Jeremy Busby sets up a metal specimen for testing to discover the mechanical properties at a high temperature. This is an important part of evaluating and qualifying materials for service in nuclear reactors.

“In those classes, there was a lot more than just math, derivations and theory,” Busby said. “It was about the discipline and rigor needed to work through these problems. We were expected to copy our notes to engineering paper in fine print and derive all the equations. It was a lot of work, but it reinforced a mentality of being meticulous in your thought process. I hold on to that notebook as a reminder to be diligent and thorough in what I’m doing, to focus on the details.”

His first forays into engineering were mechanical in nature. Busby loved fixing farm equipment at his family’s hog and cattle operation outside of St. Francis, Kansas, (then population 1,500) in the northwestern corner of the state.

“Growing up on a farm in a rural community nurtured a willingness to tinker with things, to dive in with a set of tools and figure out how something works,” he said. “As an engineer, you frequently have to devise a solution with what you have around you. I think about that a lot, how my parents, my grandparents, my uncles and others in the community taught me how to solve problems in a resourceful way.”

With three uncles who graduated from K-State and a family who cheered for the Wildcats basketball team, attending college in Manhattan was a natural fit. Busby arrived on campus intending to pursue a degree in architectural engineering. During his first year, he took a survey course designed to introduce engineering students to the various disciplines within the field. That was when he learned about nuclear engineering. One year later, he’d switched majors.

Nuclear engineering allowed Busby to build upon some of the aspects he enjoyed about architectural engineering while incorporating the advanced mathematics he loved. After earning his bachelor’s at K-State, he went on to earn his master’s and Ph.D. in nuclear engineering at the University of Michigan where he primarily studied materials science and radiation damage.

When he started at Oak Ridge National Lab in 2004, Busby was working on NASA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, a nuclear-powered satellite designed to explore the icy moons of Jupiter, namely Europa. The revolutionary multi-billion dollar probe was to be powered by a small fission reactor. Ultimately deemed too ambitious by NASA officials, the project was scrapped in 2005.

“Even though the mission got canceled, as these things sometimes do, it was thrilling to be a part of that effort,” Busby said.

Busby received the Presidential Early Career Award for Science and Engineering in 2010 for his research leading to the development of high performance cast stainless steels. In 2011, he was awarded a Secretary of Energy Achievement Award for contributions to the DOE’s response to the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident.

“I’m particularly proud of my role in supporting the U.S. government’s response to Fukushima,” Busby said. “It was very rewarding to be part of that team, pulling together the best ideas from all over the country to help the Japanese. I learned a lot in those few weeks.”

Rushing to mitigate damage after disaster strikes — in Fukushima’s case, the accident was caused by an earthquake-triggered tsunami — is most people’s idea of nuclear engineering. But from Busby’s perspective, that’s a narrow view often shaped by theatrical portrayals of nuclear engineers in pop culture.

“Nuclear engineering is a broad discipline that covers a lot of areas,” Busby said. ““It includes energy, fusion and nuclear power production but there also are national defense aspects as well as opportunities for medicine and cancer therapy diagnostics that are enhanced by nuclear engineering. I didn’t really appreciate how diverse the field really was until I was in grad school, and I’m still learning more about some of those areas today.”

Earlier in his career at the national lab, Busby was working on projects related to the safety and performance of nuclear power plants. In his current role, he’s charged with administrating the mission to be a leader in the science of isotopes, as well as the production of isotopes for security and medical applications. Oak Ridge produces, purifies and ships more isotopes than any place in the world — hundreds of isotopes used in medicine, research, industry and space exploration.

Ever had TSA swab your carry-on bag to check for explosives in the airport security line? The isotope that makes those detectors work is produced at Oak Ridge. Radioisotopes developed there are frequently used in medical diagnostics. In the rapidly growing field of nuclear medicine, certain radioisotopes deliver potent treatment targeted to cancer cells, preserving the healthy surrounding tissue. Like many, Busby has experienced that kind of treatment in his close family.

“Because of those personal experiences, being part of a mission to develop solutions to help enhance and extend the lives of others means even more to me now,” he said.

This story appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of K-Stater magazine.