Pioneering computer scientist Patricia Palombo ’58 helped launch the first American into space

On May 5, 1961, Patricia Palombo ’58 watched, along with the rest of the nation, as NASA astronaut Alan Shepard was launched into suborbital flight aboard the Project Mercury capsule he’d dubbed Freedom 7. The long-awaited flight of the first American in space — Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space on April 12, 1961 — bolstered the country’s commitment to space exploration and led to President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 declaration that American astronauts would “go to the moon in this decade.”

Palombo recalls wearing her coat, gloves, and fur-lined boots as she shivered while awaiting liftoff in an unfinished building at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Originally scheduled for May 2, the launch was delayed due to inclement weather, and Palombo and her IBM colleagues spent three nights on the floor in their sleeping bags.

“It was not enjoyable,” Palombo says. “We were all exhausted when launch day arrived and tremendously relieved when liftoff finally came. As soon as we heard there was liftoff, we all cheered. We were aware of each stage — launch, separation, flight rotation, reentry, and splashdown. With every stage, everyone was screaming.”

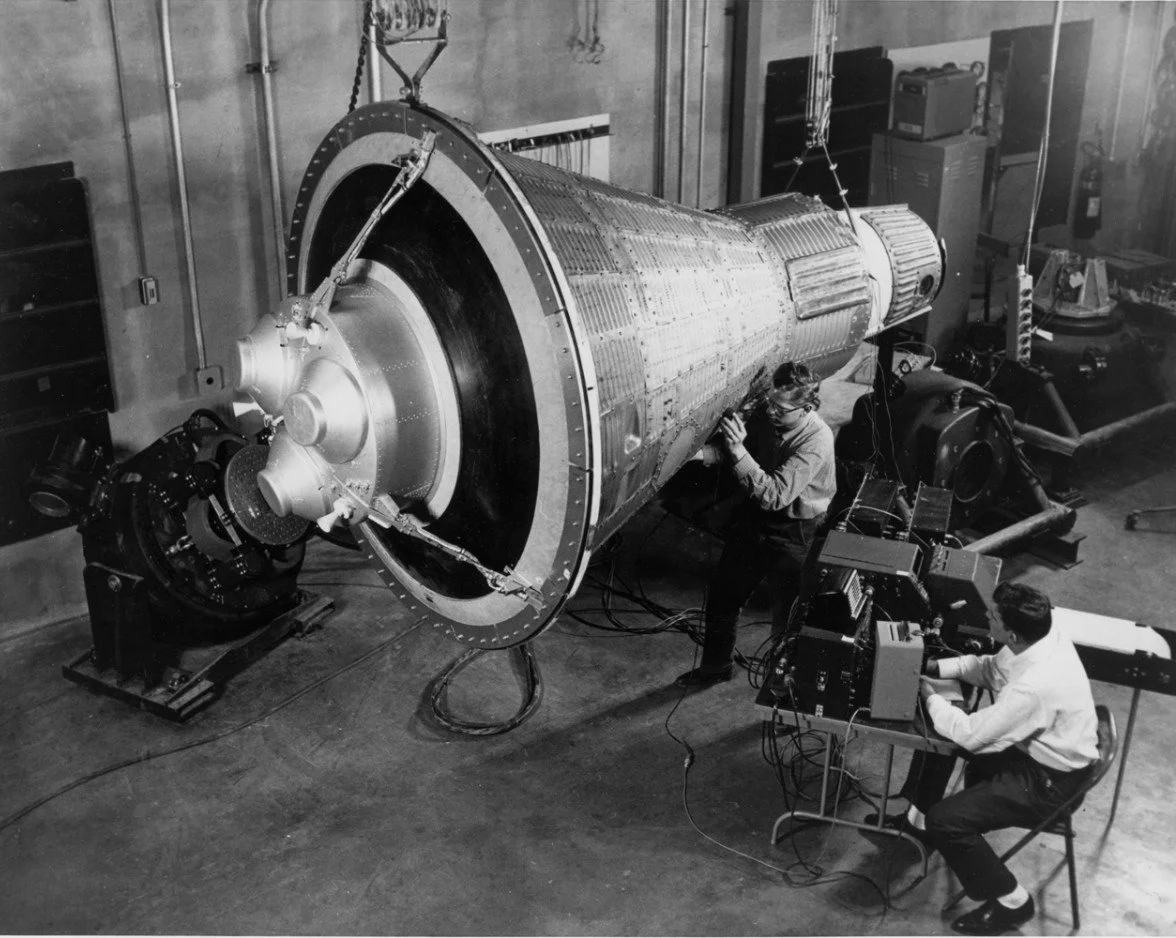

As a computer programmer for IBM, Palombo was part of a team that developed technology to track the spacecraft and provide information to Mission Control in Cape Canaveral, Florida, in real time. She wrote in Fortran, a programming language developed by IBM in the 1950s that was especially suited to numeric computation.

“My work primarily focused on the reentry phase, which consisted of tracking the capsule and performing the all-important computation of the spacecraft’s impact point after reentering the atmosphere,” Palombo says. “The impact point computation was continuously refined as new radar observations were transmitted — all with only 32,000 pieces [32Kb] of storage.”

Though she cites her contributions to Project Mercury as the highlight of her professional career and one of the most incredible experiences of her life, Palombo never dreamed she’d play a part in the early days of America’s manned spaceflight program when she enrolled at Barnard. Raised on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Palombo exhibited an aptitude in both math and music from an early age. Her mother took her for piano lessons twice a week and to concerts at Carnegie Hall on weekends. She attended the High School of Music & Art, where she learned violin and played in the school orchestras.

Her father stoked her love of numbers by sending her math problems to solve while she was away at camp — “It was my favorite camp activity,” she says. He also instilled a love of baseball, specifically the Yankees, and together they would calculate the players’ batting averages, pitchers’ earned run averages, and team standings during the games.

Palombo knew she wanted to stay in New York City for college and attend a small liberal arts school. With Columbia College across the street and, at the time, the Juilliard School a few blocks uptown, she saw intriguing possibilities to enhance her studies at Barnard, where she was one of two math majors in her class. While the math she learned in college influenced her approach to logical reasoning, creative thinking, and problem solving, she also appreciated her many stimulating courses in the arts.

“Three professors fostered my love of the arts at Barnard,” she says. “Julius Held opened my eyes to magnificent works of fine art. Barry Ulanov in philosophy taught courses in logic I adored. David Robertson showed me that Shakespeare was the ultimate genius.”

Because computer science courses weren’t offered anywhere in 1958, Palombo received her training in software development working at IBM on the IBM 650, the first mass-produced computer in the world. She used punch cards to input data, with each card holding one instruction for the computer to execute. The solution of a problem required a group of instructions, or a deck of cards, in sequence, called a program. To successfully write a program, each problem was analyzed and broken down into individual steps.

“My math training was perfect for this process,” Palombo said. “It was the beginnings of the computer era, and I felt like a trailblazer. Understanding the inner workings of a computer was invaluable to me in my career as a software developer. This connection is lost today with the higher-level programming languages now in use.”

Her work on Project Mercury continued after Shepard’s first flight. She also contributed to America’s first-ever crewed orbital spaceflight, when astronaut John Glenn circled the Earth three times, on February 20, 1962, on Friendship 7. Once NASA built the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Project Mercury relocated there, ending Palombo’s work on the space program due to her own family considerations. “It was excruciatingly painful for me to have to leave the program. Perhaps in today’s world with remote work, it would have been possible [to stay on],” Palombo says.

She went on to earn a Master of Music in piano performance from the University of Maryland before returning to IBM’s Advanced Technology Department, where she researched artificial intelligence and wrote experimental programs that paved the way for significant accomplishments in the field. Her formidable achievements were recognized in 2012 when she earned one of the first NCWIT (National Center for Women & Information Technology) Pioneer Awards. When she reflects on her varied career, it’s her work on Project Mercury that resonates most deeply.

“We were on the frontier of computer science,” she says. “The challenge was tremendous; the results breathtaking. Mathematicians, engineers, and other scientists all worked together in a spirit of cooperation that I’ve never encountered since. If we detected an error, no one pointed fingers. We huddled together to solve it because we knew we were on the cutting edge of technology.”

This story appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of Barnard Magazine.