Tyler Trent was diagnosed with bone cancer twice by age 18. He’s had nine major surgeries in the past three years. Now the Purdue freshman and die-hard sports fanatic is determined to live life on his own terms, come what may.

Tyler Trent knows the statistics.

According to the American Cancer Society, about 450 children and adolescents are diagnosed with osteosarcoma in the United States every year. About 2 percent of all childhood cancers are osteosarcoma. If treated before it spreads, the five-year survival rate is between 60 and 80 percent. Recurrent osteosarcoma occurs in 30 to 50 percent of patients with initialized local disease. If the disease has spread to the lungs, the long-term survival rate is about 40 percent. Once it spreads to other organs, chance of survival drops to 15 to 30 percent.

The 19-year-old freshman from Carmel, Indiana, is majoring in information and business analytics with minors in journalism and statistics and dreams of a career in sports analytics. He can’t help but study the numbers, scary as they may be.

“The life span of people who have gotten cancer twice is pretty short,” Trent says. “I’ve seen others around me die from cancer at a very young age. It’s a reality. I would say I’m content with the fact that if I die, I die. And that’s the way the Lord wants it to be. But I’m going to live every day I can to the fullest and impact people as much as possible.”

Tyler Trent knows the statistics. But as a die-hard sports enthusiast and a lifelong Cubs fan, he also knows that everyone loves a Cinderella story. And everybody’s rooting for the underdog.

‘This is not good’

A determined, willful child, Trent has always had trouble saying “no.” His parents, Tony (A’91) and Kelly Trent, describe him as responsible and task oriented; a doer who likes to get things accomplished. “If he has a goal, there’s not a whole lot that stands in his way,” says Kelly. “There’s just no arguing with him. He’s going to figure it out.”

Nicknamed “smiley” as a child, Trent’s frequent, dazzling grin enthralls, cracking his face wide open. He has the kind of affable, easygoing demeanor and natural charisma that draws others to him. He’s the guy who’s never met a stranger and is always up for an adventure. He’s a natural leader who has always lived in the center of the action, surrounded by friends.

“I’m a really busy human being,” he says. “I’m of the mindset that sleep is a useless thing because I feel like it’s a waste of time. That’s just how I operate.”

It was a warm, sunny day in June 2014 when Trent shattered his right arm into a zillion pieces. He didn’t realize it at the time. An active, 15-year-old with a mop of thick, curly hair, Trent was playing ultimate Frisbee at a friend’s birthday party when he felt a pop followed by incredible pain so searing that he collapsed on the ground. He’d been feeling some soreness in the arm playing basketball all summer but dismissed it as a pulled muscle. In the weeks following the Frisbee incident, Trent visited family over Fourth of July weekend, attended leadership camp, served on a mission trip in downtown Indianapolis, and headed to Kings Island amusement park. When he returned, Kelly dragged him to get X-rayed.

“The doctor wasn’t in the room 15 seconds before he looked at the X-ray and turned around shaking his head,” says Kelly. “He went straight to the point. He just kept repeating, ‘This is not good. This is not good.’”

A follow up MRI and biopsy confirmed the worst — cancer. A tumor had taken root within Trent’s bone, feeding off of it and weakening it. That tumor had essentially been holding his splintered bones together for weeks. At 15, Trent was aware something was wrong. Tony and Kelly took a few days to process the information and decide how to share the diagnosis with their son. Trent remembers his parents calling him into their room. His younger brothers, Blake and Ethan, were there. Everyone was crying.

Trent had been reading his Bible that morning and he kept going back over the same verse, 1 Thessalonians 5:16–18, “Be joyful always, pray continually, give thanks in all circumstances, for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus.”

“People were telling me how much of an inspiration I was, and I was like, ‘I’m over here on antidepressants trying to kill myself. I’m a train wreck.’”

“It really spoke to Tyler. I think that gave him comfort,” says Kelly. “Once he accepted it, and he’s like this all the time, he says ‘This is what it is. I can’t change it.’ But he struggled a lot. Cancer was really hard on him the first time — emotionally and mentally, really hard.”

Photo courtesy of Tyler Trent.

What few outside of his inner circle know is that there’s a burden to being the embodiment of others’ inspiration. That Trent hasn’t always felt strong or brave. That it’s exhausting being smiley all the time. That he’s staved off dark demons on his journey. “There’s always more than what appears on the surface,” he says.

That first time around, doctors weren’t sure if his arm could be saved. If the tumor didn’t respond to treatment, they would have to amputate. It was all too overwhelming for the outgoing teen who never slowed down.

“Once I was diagnosed with cancer, I came to the conclusion in my mind that if the cancer didn’t kill me, I would,” Trent says. “People were telling me how much of an inspiration I was, and I was like, ‘I’m over here on antidepressants trying to kill myself. I’m a train wreck.’”

Tony and Kelly remember that harrowing time. “He brought me a knife and said, ‘You need to keep this,’” she recalls. There were nights that Kelly slept on her son’s bedroom floor because they just weren’t sure what else to do. “The first time, I was a mess,” she says. “You’re distraught. It’s a very helpless feeling.”

When Kelly wasn’t sleeping on Trent’s floor, she was looking in on him in the middle of the night. If he was upstairs alone for too long, she’d run up and check.

“It was a crisis for all of us,” Tony says. “One of the things that a father does for his family is to be a protector and a provider. When you can’t do anything to help your child, you feel like you’re failing as a father. You have to relinquish what you perceive to be control. You learn a lot about yourself and about your faith. You learn what you truly believe in.”

Tony and Kelly say cancer changed their relationships with friends and tested their marriage. Even though they had a network of supporters in their church and Trent’s small, close-knit high school, they still felt painfully lonely.

“When we first went to the hospital, they told us that 90 percent of marriages don’t make it when something like this happens, and I can see why,” Tony says. “It’s really hard, and it breaks families apart.”

‘It was really, really hard’

The family threw a party at their house for Trent’s 16th birthday. It was September 2014. He’d been undergoing intense chemotherapy treatments for about two months. It was meant to be a joyous occasion. Everyone came, but because of the chemo, Trent wasn’t the same kid.

“It was a disaster,” says Tony. “He was upstairs all by himself. He ended up in the bathroom crying. Chemo changes your brain and how you think. The term is ‘chemo brain,’ and you just don’t think right. His friends didn’t understand; they just thought, ‘What’s wrong with Tyler?’ Adults don’t know how to handle it, let alone 16-year-old kids.”

Jake Heinzman, a freshman in the College of Engineering, was one of those friends at the disastrous birthday party. The two have known each other their entire lives. Heinzman was one of the friends who stuck by Trent in the hospital when things were really bad. “He would go through bouts of chemo and be in the hospital for a week at a time,” says Heinzman. “I could never fully comprehend it, but I understood that it would be very lonely, so I wanted to help him with that. I was at the hospital a lot.”

They would watch videos online, and Heinzman organized a group of friends to come in and play board games together. “It’s interesting because Tyler got cancer at the point in life where teenagers are changing into young adults, so our interests were changing,” Heinzman says. “It was so difficult because you know he’s going through something really, really hard that you’ll never understand. You can’t really help him; you can only be there for him. It was really, really hard for me.”

It was hard on everyone. But Trent pulled through, arm intact. He underwent an 8-hour surgery in October 2014 to remove the tumor and mess of shattered bone. The doctors completely replaced his shoulder and humerus all the way down to the elbow. The top half of his right arm is all titanium. After an additional five months of chemotherapy, he went into remission in April 2015.

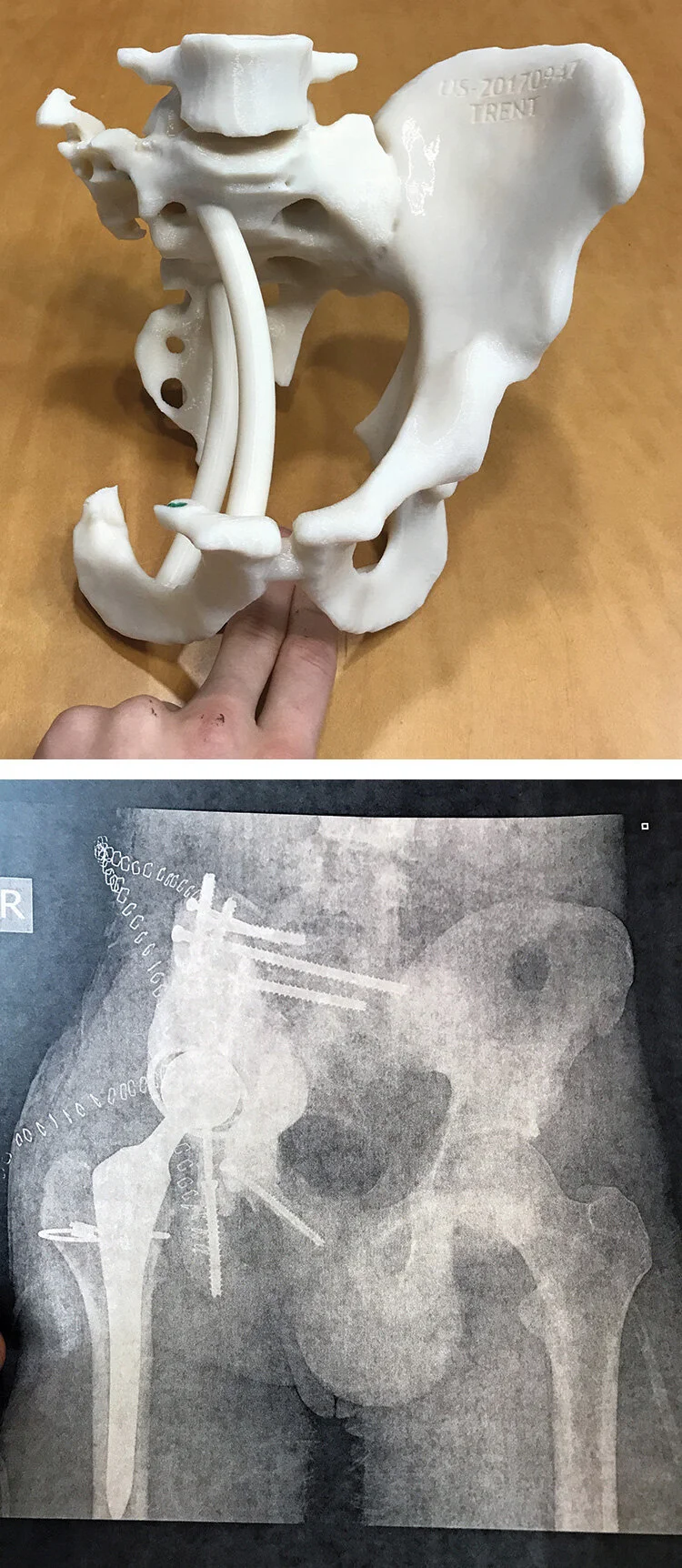

Tyler Trent started the school year with a temporary pelvis constructed out of bone cement and metal screws. In December, he underwent another surgery to have a prosthetic pelvis implanted in his body. Photos courtesy of Tyler Trent.

During his time undergoing treatment at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis, Trent befriended Angelo Wilford from Gary, Indiana, who was being treated for a blood sarcoma. The IU Northwest student was a year or two older than Trent, but when you’re in a hospital that treats children, you feel pretty old at 16. The two entered remission about the same time, but Wilford’s cancer returned — twice. He died in December 2016 at age 20.

“Angelo had a profound impact on my life,” says Trent. “He always had this mantra, ‘Don’t complain.’ No matter the circumstances, there is someone who is struggling more than you are, who has it worse off than you do. That plays a lot into how I approach things now and how I live my life. My default response to people who ask how I’m doing is ‘Can’t complain.’ There are things I could complain about, but I’ve been blessed in so many ways, the things I could complain about are small comparatively.”

It was shortly after Wilford’s death that Tyler began to fear his own relapse. On a family vacation in Florida in January 2017, he was playing spike ball on the beach when he felt pain in his groin. He saw a doctor, who initially dismissed it as a pulled muscle. Nothing showed up on the X-ray. He was told to ice it for a couple weeks and take it easy. But things didn’t get better; they got worse. Trent developed a significant limp and pushed for an MRI. The scan revealed a tumor sitting on the inside of his pelvis, reaching down into the right hip socket. The bone had hidden the tumor in the X-ray. It was April. He’d had a whole summer planned — a vacation in Colorado, a mission trip to New Zealand, and starting college in the fall.

“It’s pretty rare to be rediagnosed with osteosarcoma. The scary thing for me at that point was that my doctors viewed my initial treatment as a failure. So they had to figure out a new way of treating me and they weren’t necessarily sure how they were going to do that.” His doctors decided on an experimental approach, mixing European methods of chemotherapy and genomic testing to target his tumor. “I told my doctor, ‘I’ll do whatever I have to do over the summer, but I’m starting school in the fall. I am not going to be set back by this.”

He underwent intense chemotherapy over the summer and, 11 days before classes started, an 11-hour surgery to remove the tumor, his right hip, and half of his pelvis. Doctors rebuilt a temporary pelvis out of bone cement and a bunch of metal screws. Five days later, Tony and Tyler drove to West Lafayette to meet with a disability advisor. Tyler vomited on the ride up.

“We got done with that meeting with the disability adviser, and Tyler looked at me and said, ‘Dad, I don’t think I’m going to be able to do it,’” Tony says. “He was not feeling well that day. But I told him, ‘Let’s not make that decision right now. Let’s just finish the day. We have a couple more days and we can make that decision.’

“Purdue did such an amazing job making accommodations for my son. In fact, the disability adviser called us to tell us she’d arranged for a parking pass and told us that if there wasn’t a parking spot where he needed one, they would make one. I remember hanging up the phone and crying because it was such a gift to be able to have him there because he wanted to be there. It encouraged him and gave him a new skip in his step — or a little hop with his crutches. I just don’t know any other university that would take such personal care.”

One of the accommodations offered to Tyler was a single room in the residence halls. But he was committed to living the normal college experience, as much as he could. “People walk on eggshells around you because you have cancer. They don’t want to offend you because you have cancer, don’t want to say something wrong or ask the wrong question because you have cancer,” Trent says. “I am super thankful to Purdue for the accommodations offered to me and the lengths at which they went in order to make sure I could complete my first semester and continue on, but at the same time, I don’t want a single dorm because I have cancer. I don’t want special treatment.”

Trent met his roommate, John Kruse — also a Cubs fan — on a Facebook group for students looking for roommates. Kruse is a freshman from Chicago majoring in computer information technology. They’d agreed to live together before Trent’s cancer came back.

“I worried a lot about his roommate — a lot,” says Kelly. “I was concerned because it’s a lot for someone to take on and John has handled it beautifully. It just brings my heart joy that they have hit it off so well and that John has been so accommodating and gracious and helpful.”

At the start of the school year, Trent was in agonizing pain following his surgery. “He hides it pretty well,” says Kruse. “It can be draining on him physically. He tries not to let people know how much pain he is in.” The pain didn’t stop Trent from participating in the traditional student life experience. “Certainly without Tyler, I wouldn’t be involved in Purdue sports as I am, going to all the games. Tyler turned me into a diehard Purdue fan. He’s taught me that life is short, sometimes it can be made shorter. And not to let certain opportunities pass you by.”

Freshmen Josh Seals, left, and Tyler Trent get set for Purdue’s game against Michigan Saturday, September 23, 2017, at Ross-Ade Stadium. Photo: John Terhune / Journal & Courier.

‘We thought, “Why not?”’

Trent’s story broke in September 2017 when he and fellow freshman and childhood friend Josh Seals decided to camp out in front of Ross-Ade Stadium the night before the Homecoming game. Although members of the Paint Crew have been known to camp out at Mackey Arena, it’s been awhile — if ever — that students camped out for a Boilermaker football team.

That Friday morning, Tyler attended classes before driving down to Riley for his weekly chemotherapy appointment and returning to West Lafayette to have dinner with friends and set up the tent with Seals. His doctor wasn’t crazy about the fact that Tyler camped out, but there was a front-row streak to protect.

“We figured if Purdue has momentum going into the Michigan game, it’s going to be a pretty big game,” says Trent. “It’s probably going to be one of our biggest home games. Big Ten Network was going to be on campus, so we thought, ‘Why not?’”

Trent tweeted out a photo of their tent and the local media picked up on the story. Trent became the face of cancer on campus overnight. Coach Jeff Brohm stopped by the campout the morning of the game, and Trent had a front-row seat for the first sellout at Ross-Ade Stadium since 2008. Five weeks later, he was on the field for the coin toss as honorary captain during the Hammer Down Cancer football game, raising awareness for the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research. Trent spoke at the Hammer Down Cancer luncheon the previous day.

“The first time I got cancer, I felt like I didn’t do enough with my story,” Trent says. “Now I have another opportunity to share my story, because I’m going through this thing again. How I act and what I do is going to impact people. I’m so thankful for the opportunity to have another platform, in a way, to share my story.”

The change in Trent’s outlook the second time around is remarkable considering he once told his parents he’d rather die than undergo chemo again. “He’s grown so much,” says Kelly. “As parents, Tyler holds us up. The way he has faced the second diagnosis, he has no idea how much he’s helped us handle it and be okay with it.”

Alan Karpick (HHS’83, M’83), president and publisher of GoldandBlack.com and member of the director’s advisory board for the cancer center, met Trent when he spoke at the Hammer Down Cancer luncheon.

“He was so articulate, so relaxed, so at peace with who he is and what he is — that’s what’s amazing.” Karpick says. “When you learn his whole story, what he’s had to deal with, it never comes from him in moments of disdain or pity. For a college freshman to articulate a mature and quietly impassioned message was very impressive to me. He makes you feel very comfortable in his presence.”

Recently, Trent was invited to join the cancer center board as its first-ever student board member.

“Tyler is the poster person for why the cancer center needs to do research,” says Karpick. “Every person that deals with the scourge of cancer is a person of light, a person of potential and possibility. The better research that can get done, the more we can make sure a light like Tyler can shine as long as humanly possible. His attitude is, ‘What can I do to help? What can I do to be part of the solution?’ He just wants to contribute.”

Tyler Trent and his father, Tony, traveled to Iowa City for the Purdue–Iowa game where they met with patients at the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital. Photo courtesy of Tyler Trent.

When Purdue played Iowa in November, Trent and his father made the trek to Iowa City to participate in the most heartwarming new tradition in college football. At the end of the first quarter, 70,000 football fans in Kinnick Stadium turn and wave to the top floor of University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital. The Trents spent time touring the hospital and visiting patients before the game.

“It was one of the greatest things I’ve ever done with my child,” says Tony. “I don’t know if I’ll ever get to do it again with him, and just to know how those parents felt up there, the pain and the struggle … it was just such a blessing, and I am so thankful that we made the time to do it.”

After the game, they hightailed it back to West Lafayette so Trent could catch the last 12 hours of the Purdue University Dance Marathon, a student-run event that raises money for Riley Hospital for Children. He was one of the featured speakers Sunday morning. He followed up his whirlwind weekend with a trip to Riley for chemo on Monday.

If you think he sounds nuts, you’re not alone. “Sanity would be the last word I would use to describe myself,” Trent says. “Ninety-nine percent of the time, commitment trumps reasoning in my mind.”

Which is how Trent and Kruse started plotting to attend a bowl game when it looked like the Boilermakers might have a shot at postseason play for the first time in five years, despite Trent being scheduled for another major surgery December 13, this one to implant his prosthetic pelvis.

“Once it was clear that Purdue was going to make a bowl game, we had our eyes glued on where they were going, our fingers crossed,” Kruse says. “Hearing it was in California, it was cool but kind of a worry, too. Originally, we were going to drive. Just coming off surgery, they wouldn’t want Tyler sitting in a car for 32 hours.”

One of Trent’s high school teachers started a GoFundMe to cover the trip to the Foster Farms Bowl. Word spread and a Purdue alumnus arranged for complimentary lodging in downtown San Francisco — “The nicest hotel I’ve ever stayed in my life,” Trent says. The Boilermaker Special was waiting out front when they arrived, ready to take them on a ride through the city. It was the trip of a lifetime for Heinzman, Kruse, and Trent.

“It was an amazing time,” Heinzman says. “We stayed out there for a week, saw the sights. It was really chill. We were able to do whatever we wanted.” Still, the friends worried about Trent pushing himself so hard just two weeks after surgery. “It’s tough with Tyler. He doesn’t say no to stuff when he probably should. I could definitely tell when there were times when he was tired. We would ask, ‘Are you feeling up to this? Are you sure?’ He always wanted to keep going.”

The fact that cancer has brought him opportunities he otherwise would not receive weighs heavily on Trent. He is cautious about the appearance that he’s exploiting his disease for personal gain, which is why he created a spreadsheet to track trip expenses and vowed to donate any remaining funds to Riley.

“Everything he does is for someone else,” Kruse says. “Tyler is always looking out for the people around him. If anything, Tyler is helping us. Being with him is a perk for everyone.”

‘It’s a mental battle’

Former North Carolina State basketball coach Jim Valvano gave a speech less than 10 weeks before his death from cancer. He talked about the importance of hope, love, and persistence and spoke the famous words “Don’t give up; don’t ever give up.” The phrase became the motto of the V Foundation, one of the nation’s leading cancer research funding organizations.

“Jimmy V is a role model for me in the way that he fought cancer,” Trent says. “Half the battle, perhaps more, of anything hard you’re going through, it’s a mental battle. Yes, I have pain, but it’s how I deal with that pain mentally that’s going to affect how my day goes.”

In his second semester, Trent can still be found in the front row, now in Mackey Arena for what has been an incredible season for the men’s basketball team. And if the Boilers make it to the Final Four? For Trent, it’s not a matter of if it happens, but when. He’ll be there. “My dad and I have already talked about it,” he says. “San Antonio’s not that far. It’s what, a 16-hour drive? A lot closer than California.”

Trent is looking toward the future. He’s in his final months of chemo. The precision genomics protocol will continue through June. His hair has started to grow back. He’s begun working out with Kruse at the CoRec to build strength on his right side. “We joke that Strong Tyler’s coming back,” Kruse says.

He started covering athletics for the Exponent this semester, the first job in what he hopes will be a career in sports analytics. He and Heinzman are producing a weekly podcast, Completely Unrelated, from the radio station in Wiley Residence Hall. He has dreams of having a family one day, although he realizes that cancer affects his dating prospects. As for his prognosis? Unknown. Trent is a black-and-white thinker to begin with. He’s undergoing experimental treatment. Knowing how things turned out after his first bout with cancer, it’s hard to be overly optimistic the second time around. Despite that, it would seem he’s laid his old demons to rest, for the most part.

“I don’t carry a knife with me anymore,” Trent says. “I used to carry a knife all the time, but I don’t trust myself. Suicide isn’t something I’m currently dealing with, but there are still dark days, and we default to our most human tendencies when we’re in those hard times.”

Trent recalls a story about a man who jumped from the Golden Gate Bridge in the 1970s. He’d left a suicide note in his apartment stating that if one person smiled at him during his walk to the bridge, he wouldn’t jump. No one did.

“I hope a lot of people aren’t in that situation, but if a smile is going to make someone’s difference in the day, then I’m going to do it,” Trent says. “That’s my idea of living life to the fullest. It’s not the camping out for a football game; it’s the smiling at people you pass by on the way to class or being considerate of other people, looking out for their needs, listening to their stories.

“Everyone has a story. And there just needs to be people in this world willing to listen to that story. Every story matters. We are shaped by our experiences, and we are the people that we are because of the things we’ve been through. I’m very confident that I would not be the person I am today without having gone through cancer twice.”

“We are shaped by our experiences, and we are the people that we are, because of the things we’ve been through.”

Tyler Trent died at home on January 1, 2019. He was honored with a candlelight vigil held on the Purdue Mall one week later. It was attended by 2,000 people.

This story appeared in the Spring 2018 issue of Purdue Alumnus magazine.

Photos by Charles Jischke.